How Britain Fell In Love With Cats

Exclusive Interview with Kathryn Hughes

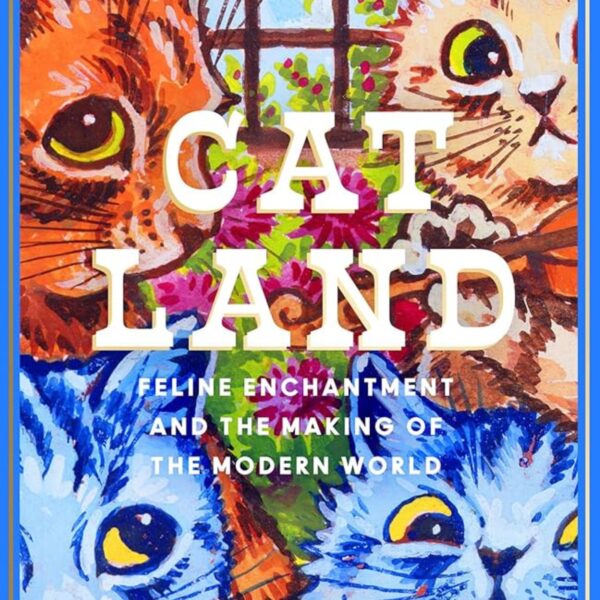

Catland, the wonderful book by Kathryn Hughes, is a delightful dive into the late Victorian and Edwardian world where the art of Louis Wain helped transform cats from tolerated rodent controllers to adored and pampered pets. Here Kathryn tells us about herself, her work and how her own cats feel they could have made a better job of the book themselves.

If a close friend was asked to describe you in a couple of sentences, what might they say?

“Kathryn is neurotic, compulsively punctual, spectacularly untidy and a workaholic. On the other hand, she is also kind, polite, conscientious, and finds other people deeply fascinating to the point of being nosy.”

Your past books were about humans, why change to cats?

Honestly, it’s the same thing! I wanted to explore the way that Victorians and Edwardians - the sort with two legs - began to think of their cats as people, or at least as pets. Before this, felines had been regarded as anonymous servants whose main purpose was keeping domestic and industrial spaces free of rodents.

Whereas once they didn’t have names but were just called ‘puss’ or ‘kitty’, now they began to be given human names like ‘Oliver’ and ‘Mabel’. Instead of eating what they could catch or steal – now pet cats began to be given regular meals with food specially bought for them. People provided baskets to sleep in, soft cushions and the occasional human lap on which to doze. Where once they had skulked in sculleries, now they were welcome into the drawing room.

Humans also found their lives expanding. Middle-class women started breeding pedigree animals which they sold for profit. It was an excellent way of making an income without compromising your ladylike status. Writing about cats also offered a new income stream. One clergyman’s daughter, Miss Frances Simpson, became wealthy by writing advice columns and even books about how to make money from your ‘pussy’ (yes, that was the word she used).

New industries sprung up too – specially shaped baskets to carry cats in, dried food (courtesy of Spratt’s), special soil for their litter boxes which had to be imported from Japan. Cat capitalism.

Who was Louis Wain, and would we have a world and internet packed with pampered and beloved cats without him?

If you see a Louis Wain cat picture you will instantly recognise it, even if you can’t quite recall the artist’s name. From 1880 until his death in 1939 Wain drew anthropomorphic sketches, cartoons and paintings of cats for newspapers, magazines and Christmas cards. He was everywhere and we have him to thank for the ubiquity of cat memes all over the internet. Dressed to the nines in straw hats, blazers, puffed-out bustles, and sailor suits, Wain’s cats take advantage of the newly glitzy world of the late Victorians and Edwardians. They play cards at their club, go boating on the river and take in a show at the theatre. Kittens go to school and make mischief, while harassed cat mamas sit by the fire and do the household mending. Daddy cats retreat behind the Cat News at the breakfast able and try to block out the noise and smells of domesticity.

Wain’s style was instantly identifiable and he became a household name as ‘the Man who Draws Cats’. He had a side gig producing postcards and annuals which meant his images found their way into nearly every British home, not to mention in Europe and America too. His images were used by companies to advertise everything from washing powder to chocolate biscuits. Wain’s portrayal of Catland changed the way that people thought about their pets. It was now possible to imagine that, when your cat slipped out of the backdoor at dusk, it was into a parallel world of partying, courtship and even seaside frolics. Wain gave a shape and colour to the idea that cats enjoy a secret life in parallel to ours. At the same time, he also provided a sly commentary on the human world. In Catland, cat people fall out with one another over money, they two-time their partners and always cheat at tennis.

Have other artists or writers affected the world's view of cats?

Wain reigns supreme in terms of illustrators. That isn’t to say that a lot of artists don’t put cats in their paintings – Gaugin, Monet, Lucian Freud, Gwen John to name a few - but in these cases the cats tend to be doing a lot of heavy symbolic lifting, representing lust and treachery or, conversely, peaceful domesticity.

In terms of authors I think the choice is wider. My favourites would be:

The Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll)

Orlando the Marmalade Cat, (Kathleen Hale)

Nameless Narrator of I am A Cat (Natsume Sōseki)

The Cat in the Hat, (Dr Zeuss)

Pet Sematary (Stephen King)

Old Possums Book of Practical Cats (T.S.Eliot)

The Cat Who Walked By Himself, Just So Stories (Rudyard Kipling).

What is your own relationship with cats?

My grandmother was a breeder of Blue Persians, although when push came to shove she could never bear to part with them so there were cats everywhere – on the table, in the coal bucket, rifling through the drinks cabinet. She had a lot of Louis Wain annuals too, so that is where I first heard his name. Full disclosure: they terrified me, both my grandmother’s cats and her Louis Wain pictures. I always felt there was an undertow of cruelty.

I have two cats, Ted and Maud. They are indoor cats because I live on a busy London square and it would be dangerous to roam. They are the essence of entitled. If they saw a mouse they would be terrified and would expect me to catch it and despatch it. They wouldn’t dream of eating it, since they have multiple allergies (or say they do). When I was writing Catland they were interested in sitting on my notes to keep them warm but, so far, have been unimpressed by the final book. Deep down, they think they could have made a better job of it themselves.