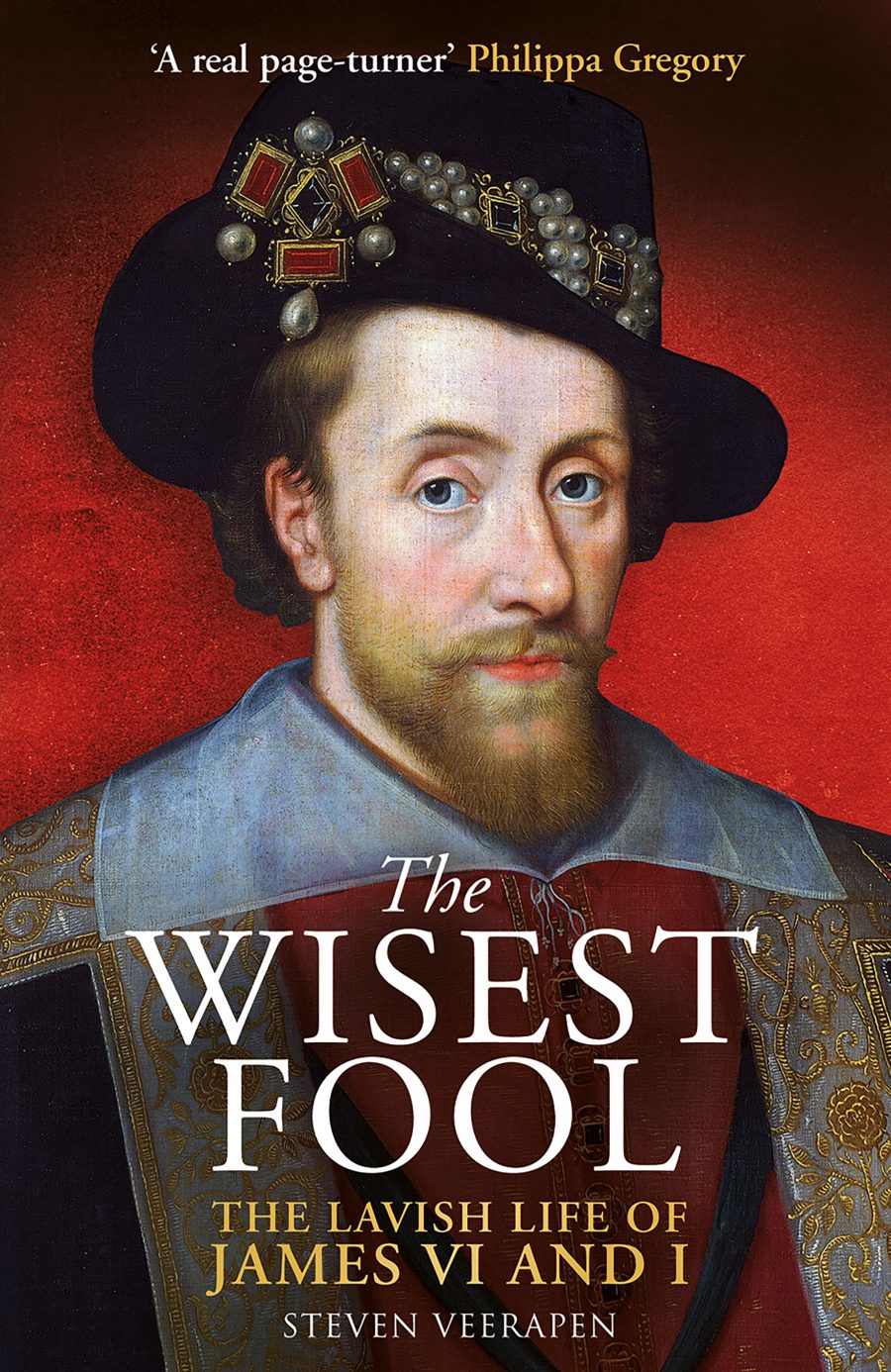

The Truth About James VI

Drooling fool or much under-rated monarch? Steven Veerapen takes a fresh look at James VI and I, derided by his enemies as the smelly, decadent, “witch” slaughtering king derided as the “wisest fool in Christendom”. We asked the author to tell us a little more about his views on the Scottish king who succeeded to the English throne and established a new dynasty after the death of Elizabeth I.

What were the challenges facing a Scottish monarch trying to stamp his authority on the English court?

James faced difficulties both of his own making and not. For one thing, he really hated London and grew increasingly fond of decamping to the country. He could be something of a ‘distancing’ monarch, who kept the hoi polloi at arm’s length (or further, if he could get away with it). Yet he was more than capable of rising to the occasion at state events; he loved parading around weighted down with jewels, rich silks and velvets. What hampered his authority was a growing sense on the part of his English subjects that he preferred to surround himself with trusted

Scots, and that he was averse to making England great again militarily. This gave rise to a lot of xenophobia – and the king’s popular son, Prince Henry, was looked up to (until his untimely death in 1612) as the coming man: the anglicised Protestant soldier-prince whom Englishmen increasingly wanted as their sovereign.

What brought James' change of heart on witchcraft and the threat from supernatural forces - and did he show any remorse for all the executions?

James seems to have imported the idea of witchcraft as a wide-scale threat from Denmark, where it was first touted as the cause of the freak storms that kept his bride, Anna, from sailing for Scotland. I don’t think James ever abandoned the idea of witchcraft as a real phenomenon. But he was a complicated man: on the one hand, he fancied himself a rational intellectual, and on the other he was subject to paranoia. He balanced this out by priding himself on sorting the ‘false’ witchcraft accusations from ‘real’ ones. Unsurprisingly, it seems he was always willing to believe witch hunts were justified when the alleged witches were said to be aiming their sorcery at his person. If he wasn’t personally threatened, he was happy to present himself as the rational debunker of malicious local disputes.

Did he prefer peaceful approaches to international issues or just not have the resources for war?

James was definitely a committed peacemaker. It’s true, he lacked the resources for wide-scale war, but on multiple occasions he could have sought handouts from parliament (and despite his straitened finances, he never quibbled to spend like a drunken yuppie on entertainments, gifts, and jewels). He’d had enough of conflict during his time in Scotland. What he really sought was the coveted role of continental peacemaker, which had occasionally been grasped at by Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey. Even through his children’s marriages, he sought a balance between religious interests, and his great goal was uniting Protestant denominations as a prelude to an ecumenical accord with Catholics. He genuinely thought that Europe, which had torn itself apart in the sixteenth century, should begin putting itself back together again. He was to be disappointed in that wish – but it was a noble dream.

Was James misunderstood or misrepresented as a person, and what do you see as his defining traits?

James has long been misunderstood and misrepresented as a smelly, slovenly coward (at best) and a loping, leering oddball (at worst). This is unfair. He lived in an age in which scurrilous political libel flourished, and he was a prime target. His desire for peace was not cowardly and he took no more personal safety precautions than did his Tudor predecessors (these being necessary in an age of political assassinations). His defining traits were a love of (in fact, an obsession with) family; bluff bonhomie and a penchant for eye-roll-inducing jokes; and an unshakeable self confidence and belief in his own divinely appointed status. James, like Henry VIII, was always right – but unlike Henry VIII, he wasn’t going to scare you into accepting he was right; he’d far rather explain in detail why you were wrong!

What do you see as his central aims - and did he accomplish them?

James’s central aims in England were universal religious peace, which history shows was impossible to achieve. His other major goal was the unification of Scotland and England into a single Great Britain, with his dynasty perpetually ruling it. This was impossible too. Aside from the fact the Stuart era ended with Queen Anne, his conception of union went far beyond what was achieved in 1707; he wanted the Scottish Kirk to fall in line with the Anglican Church (of which he was supreme governor). Additionally, he professed himself keen to see Scots Law replaced with the English Common Law, which has also never come about. In Scotland, his central aims were more successful. He wanted to defang Presbyterianism (which he did, although it would revive with a vengeance, as his son found out) and bring Scotland to something like obedience to the Crown. In the latter he did well. Despite frequent attacks by the Kirk, he played noble factions (which had become powerful as a result of repeated royal minorities, including his own) off against each other and saw off several uprisings and kidnapping attempts. One goal he achieved in Scotland, though, lasted into his reign in England. He wanted to be a patriarch. Despite his romantic preference for men, he was actively bisexual and produced multiple children with Queen Anna (though only three would survive infancy); he was no “heir and a spare” monarch. In 1603, he could congratulate himself as Scotland’s patriarchal master. In England, he could – and did – present himself as a dynast: the affable father of the nation.