Iceberg A68

Image: Iceberg A68, credit: UK Ministry of Defence 2021

Julie Laing, winner of Wigtown Poetry Prize 2022, wrote her winning entry about the dissolution of a giant iceberg classified as A68. When lockdown restrictions lifted, she spent her winnings from the prize on a trip to Iceland, seeing the inspirations for her poem firsthand.

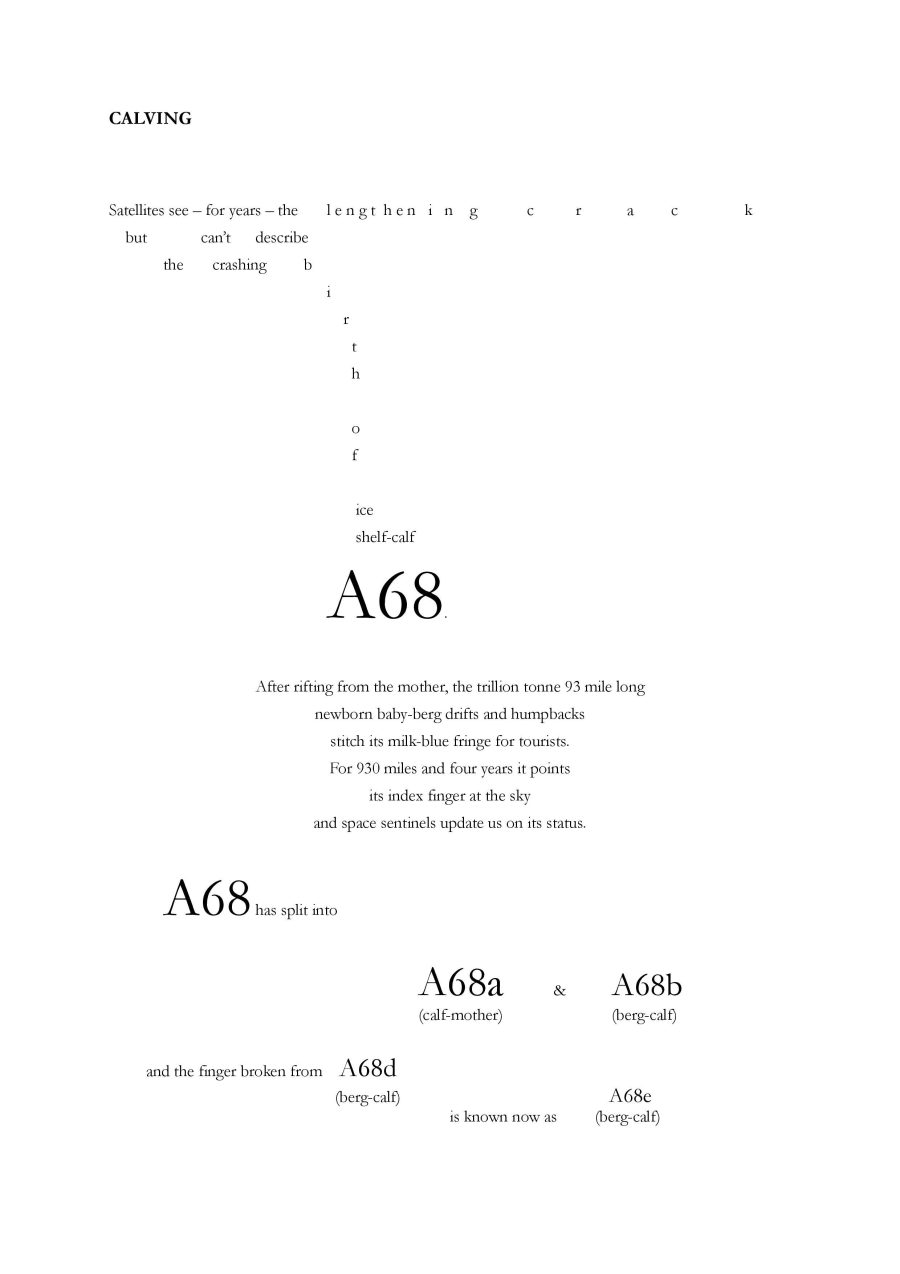

I wrote CALVING as part of an ongoing collection of poems responding to news events since 2019. In 2021, I came across reports about the demise of a giant Antarctic iceberg, labelled A68, which had become slush less than four years after breaking away from its shelf. A series of ghostly shots from space highlighted the scale and alarming pace of its lonely dissolution, but it was the analogy implied in the nomenclature ‘calving’ that intrigued me. Scientists so often come up with striking metaphors that allow us to conceptualise our world and place within it, and the idea of each berg as a young mammal – a vulnerable, sentient being – countered the starkness of NASA’s satellite images.

It seemed also to resonate with our experience of Covid at that time. As I was working on the poem, we were still trying to comprehend the impacts of lockdowns, and I think inscribed in it is something of my new awareness of how fragile and easily fragmented our social structures are.

I often use poetry as a tool to interpret concepts and environmental phenomena, and the process of researching and shaping words gave me insight to the formation and movement of icebergs and glaciers. While the story of A68 is, to a large extent, one of a predictable and natural shedding – known as ablation – the acceleration resulting from global warming is disrupting the balance between snowfall, glacial ice and seawater. I played around with the characterisation of icebergs as baby cows, and the idea that the sudden generation of a new life simultaneously sounds its death knell. On the page I used the concrete placement of characters to contrast the dispassionate view from above with the plaintive ‘moos’ of the shrinking structures. And in the process of making these ‘textbergs’ and giving voice to the melting, I became connected to the impending loss of ice.

Iceberg A68 close up, A68 breakaway, credit: Ministry of Defence

When CALVING won the Wigtown Prize in October 2022, I was already itching with a post-pandemic urgency to travel; the previous couple of years had taught us that places and experiences can become unreachable, even for those privileged enough to be able to afford to them. And glaciologists forecast that, based on the current pace of climate change, much of our more accessible ice will be gone in a couple of hundred years. This, and a conversation with the award ceremony photographer, Colin Tennant, who documents the Arctic, Antarctic and Subarctic, motivated me to visit while I could.

So I used the prize money to book a trip to Iceland, and in April saw icebergs for the first time ‘in the flesh’. At Jokulsarlon Lagoon and Svinafellsjokull glacier outlet, while witnessing them queue in slow progress to the ocean, the science came alive and I felt the shapes I had written. It’s an unforgettable experience that will find expression in future work, and it left me with new questions. Do appealing representations of the beauty and vulnerability of this environmental phenomenon fuel the burning up of air miles in pursuit of photogenic bucket list destinations? Are the individual lifestyle changes made by eco-tourists and artists meaningful enough to justify their journeys? It’s an interesting ethical discussion, brought deeper into my personal sphere by going there, and I’m mindful of the irony of booking a flight with the proceeds from a poem about a melting iceberg.

Images © Julie Laing, 2023 .

Left: Svinafellsjokull glacier outlet, Iceland. Right: 200m deep Jokulsarlon Lagoon, which appeared in 1934, with Oraefajokull glacier in the background and seals in the foreground

Since coming back, I’ve been using poetry again as a means to comprehend the inconceivable. I’m playing with unfamiliar phrases – anthropogenic global warming (ie our fault), interglaciation, heat island effect – and in doing so they’re becoming part of my reality. I reread the Alastair Reid Pamphlet Prize 2022 winner, Rain Falling by Sarah Leavesly. She too uses concrete poetry to consider our place in our environment, and I’m newly intrigued by this line: “Poets killed the moon first; they didn’t mean to, but they did.” I’m thinking about what this means to me. Does making the impossible graspable diminish it, make it easier to dismiss? Or, if I post a photograph of a glacier, or write about a black hole, do I fill your hands with it so snugly that you don’t want to let it go? Maybe, some day, our archive of words and images will have to be enough. In the meantime, recreation, when contained in the imagination, doesn’t need to be carbon offset.

Julie Laing is a Glasgow-based visual artist and writer exploring places where environmental phenomena and human experience intersect. Follow the link below to see more of her work